Supreme Court Holds that Claims for Intentional Discrimination Under Section 1981 Must Meet “But For” Causation Test

Section 1981 of the Civil Rights Act prohibits intentional race discrimination in all forms of contracting including employment. Lower courts have split as to whether a § 1981 plaintiff must prove that race was only one motivating factor among several, or whether a plaintiff must allege and prove that race was the “but for” cause of the challenged decision. In Comcast Corp. v. National Association of African American-Owed Media, et al, the Supreme Court recently resolved this split, holding that a plaintiff must prove that race was the “but for” reason for the decision. In other words, “but for” the defendant’s unlawful conduct, the decision would not have occurred.

In Comcast an African-American owned television network operator sued Comcast because Comcast refused to enter into a contract to carry the operator’s networks. During negotiations, Comcast cited to several non-discriminatory legitimate business reasons for not wanting to enter into the contract, but the network operator sued alleging that despite these potential legitimate reasons for Comcast’s position, Comcast was also motivated by racial bias. The District Court granted Comcast’s motion to dismiss on the basis that the network operator had not sufficiently alleged that “but-for” racial animus, Comcast would have contracted with the operator. The Ninth Circuit reversed, holding that a plaintiff only needs to show that race played “some role” in deciding not to enter into a contract, and that under this standard, the plaintiff had stated a viable claim. In so doing, the Ninth Circuit relied on the causation standard contained in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which was specifically amended in 1991 to provide that an employee could prove unlawful discrimination under Title VII by merely showing that race (or other protected characteristic) was a “motivating factor” in the challenged decision. The Supreme Court rejected this reasoning, noting that Congress did not specifically adopt this motivating factor standard for Section 1981 claims, although the 1991 Civil Rights Act did amend Section 1981 broadening its coverage in other respects. If Congress intended for the “motivating factor” standard to apply to Section 1981 claims, the Supreme Court reasoned that Congress would have specifically said so when it amended the statute in 1991.

PRACTICAL POINTERS:

- In many employment discrimination cases, the impact of the Comcast decision may be limited because in cases of race discrimination, an employee may also have a potential claim under Title VII. As noted above, under Title VII an employee needs only to show that their protected characteristic (race, color, national origin, sex, religion etc.) was a motivating factor in the alleged discriminatory decision.

- The statute of limitations generally is 4 years for a claim under § 1981, but an employee needs to file an EEOC charge in only 300 days from the date of the decision being challenged. This means that an employee may still sue for intentional race discrimination without filing a timely EEOC charge but must prove discrimination under the more stringent “but for” standard.

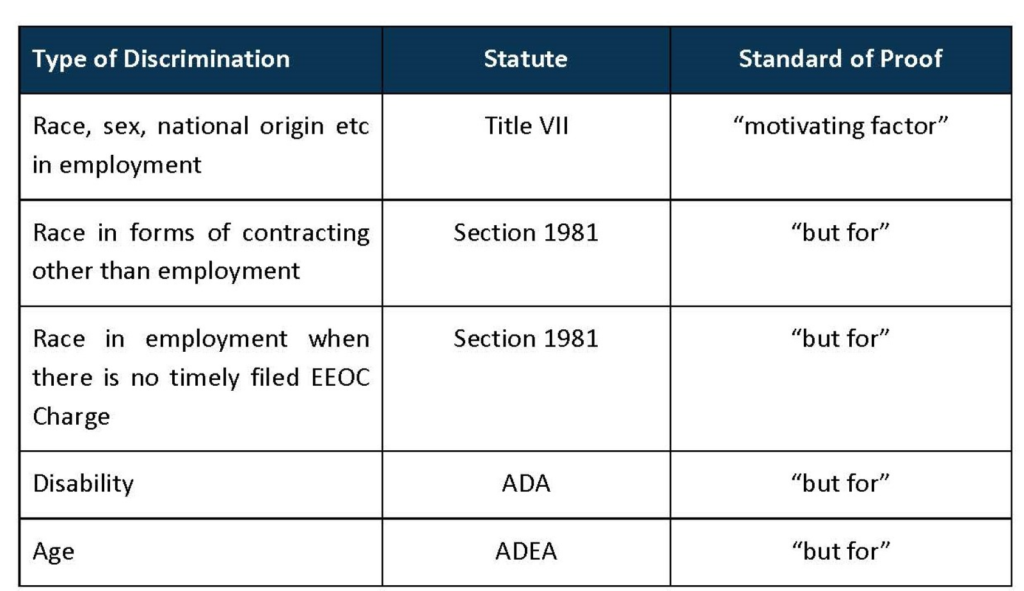

- Based on the applicable statutory language and Supreme Court precedent, the level of proof required to prove unlawful discrimination varies depending on the type of discrimination alleged: